With all the noise about fake news and conspiracy theories at fever pitch following the election, one fundamental but understated truth stands out: our trust of and even acquaintance with our neighbors is at a new low. It is no wonder that fear of “the Other” reigns in the form of bigotry, gun violence, and general resistance to giving anyone either a hand up or a hand out.

Since the 1970s, “social capital” – that is, an everyday culture based on friendly interactions – has declined significantly, according to a 2015 report by the Portland, Oregon-based think tank City Observatory. A third of us have not even met our neighbors. Between the explosion of sprawling suburbs and the use of cars, freelance work, private means of entertainment from the television to the smart phone, and the waning interest in social spaces such as public pools, libraries, bowling alleys, union halls and houses of worship, “the connective tissue that binds us together is coming apart.” With the ascent of social media, our spaces have become virtual, literally revolving around our own “faces.”

This has a ripple effect in our civic sphere with declines in community involvement and volunteership. Behind calls for increased police protection and metal detectors in our schools is a relinquishing of faith in human empathy and compassion. The entire Donald Trump phenomenon, fueled by paranoid sound bites and tweets, fans the flames of Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, racism, “terrorist” labeling of Syrians and other refugees, and anti-Mexican vitriol.

“Radical solidarity” is the solution that John Nichols of The Nation, joined by community organizer and restorative justice advocate Mariame Kaba, posited at Chicago Area Peace Action’s annual dinner following the election. This means deliberately standing in harm’s way to prevent our own government from detaining, registering, denouncing or deporting our neighbors. It means doing whatever it takes to protect our land and water as well, as at Standing Rock. Nichols recalled the famous dictum by the anti-Nazi activist Rev. Martin Niemöller:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out

Because I was not a Trade Unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me.

Where does an ordinary person begin?

I suggest you start simply: get to know your next door neighbor.

In Arvada, a suburb of Denver, a group of congregations decided to do just this following an appeal to Christian clergy by the mayor. They founded a “Neighboring Movement” that posited, “What if Jesus meant that we should love our actual neighbors?” They created a web site, The Art of Neighboring, with tried and true strategies such as literally mapping their block with names of neighbors and organizing block parties. Getting to know their neighbors, they were able to help those who were ill or isolated and to organize activities for children.

Neighborliness is fun and even healthy, according to a 2011 University of Missouri study published in Social Science & Medicine. That’s because our anxiety levels decrease as mutual trust increases.

Similarly in Skokie, the ethnically diverse Chicago suburb in which I live, block parties have been encouraged by the municipality to create ties that bind between new immigrants and old-timers, and between renters and homeowners. “Know Your Neighbor” coffees was one modest initiative (2008-2012) with a modest “kit” for any resident who wanted to host one, complete with generic flyers, brochures about local services and a voucher for a free coffee cake (regular or kosher). For the past two years, Skokie has encouraged residents on multifamily blocks to host a party, even providing games through the public library.

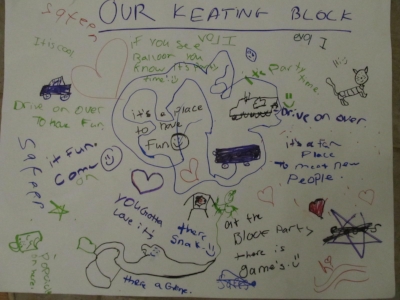

At the onset of summer, I approached my next door neighbor Yasmeen and two others, Sharon and Mercedes, about organizing a party. We decided on a Sunday afternoon in October, and to use my yard rather than block off the densely populated street. Yasmeen, who moved in two years ago and whose family comes from Pakistan, invited Urdu speakers on the block. We created a multilingual flyer in Spanish (thanks to Mercedes, who is from Peru) and into Polish (thanks to my friend Anna). Yasmeen's children and I dropped these off in vestibules and mail slots.

About eight families gathered; and over food we each brought and shared, realized that we are a resourceful and wide-ranging group of parents, grandparents and children, diverse by race, religion and nationality. In our small group alone we were working as school bus drivers and in food service, and as carpenters, artists, and cab drivers. Several Skokie Human Relations Commisison members came by to show support. We are determined to have a larger party next year -- and to share more interesting dishes that reflect our different cultures rather than ubiquitous and bland varieties of cookies and chips.

Over the summer, I mowed Yasmeen’s lawn along with my own -- the least I could do since I learned that she was overextended. Last week, I slogged home from running errands on the day of the season's first snowfall to find her entire family wiping snow off their coats after having shoveled for both of us. I thanked her, very touched, and she replied, “We are neighbors and we need to take care of each other.”

So just as the journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step, standing up for entire groups of people as an expression of radical solidarity starts with a single outstretched hand to one’s next door neighbor.